“Greater love has no one than this; to lay down one’s life for one’s friends.” —John 15:13

I never thought I’d get to see an actual American military cemetery in Europe. Picture the opening scene of the movie Saving Private Ryan with the older man in the military cemetery before the headstones.

There is power here beyond words. The force of love and sacrifice.

Sturdy gates, decorated with laurel wreaths for valor and topped by golden eagles greet the visitor. This is undeniably a place of honor and clearly revered by its nation. Before you even get into the cemetery, you see the proud American flag atop a tall flagpole overseeing its venerated graves.

A tour bus and its driver wait in the parking lot with “Beyond Band Of Brothers” written on its side.

Upon entering, we find a small group of WWII veterans and spouses exiting the cemetery. This place is still visited—and loved—by those who fought for that good cause.

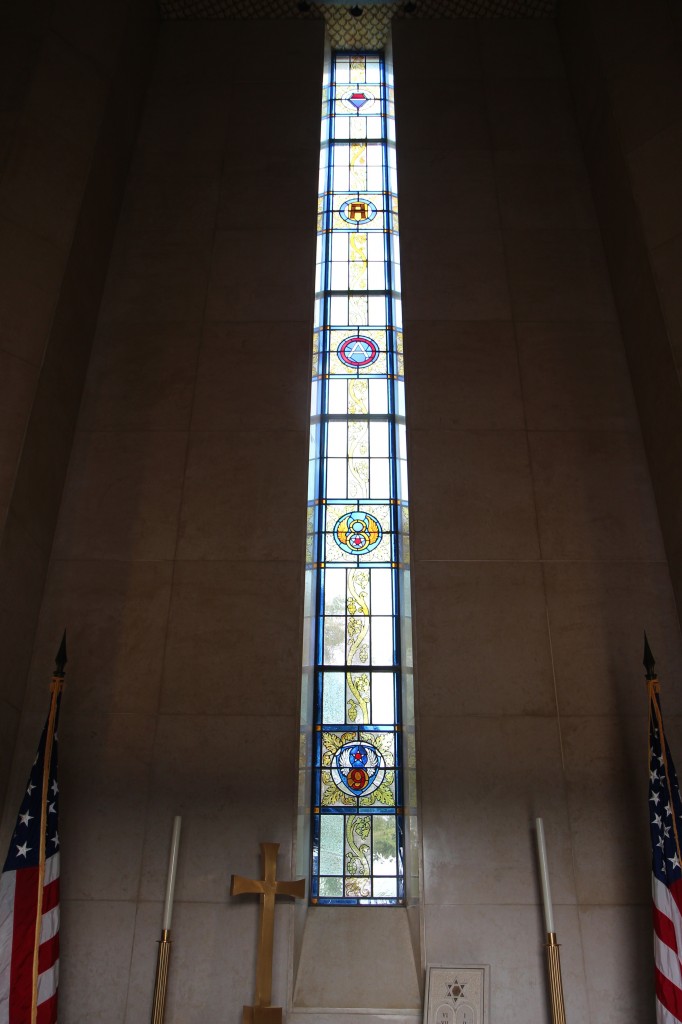

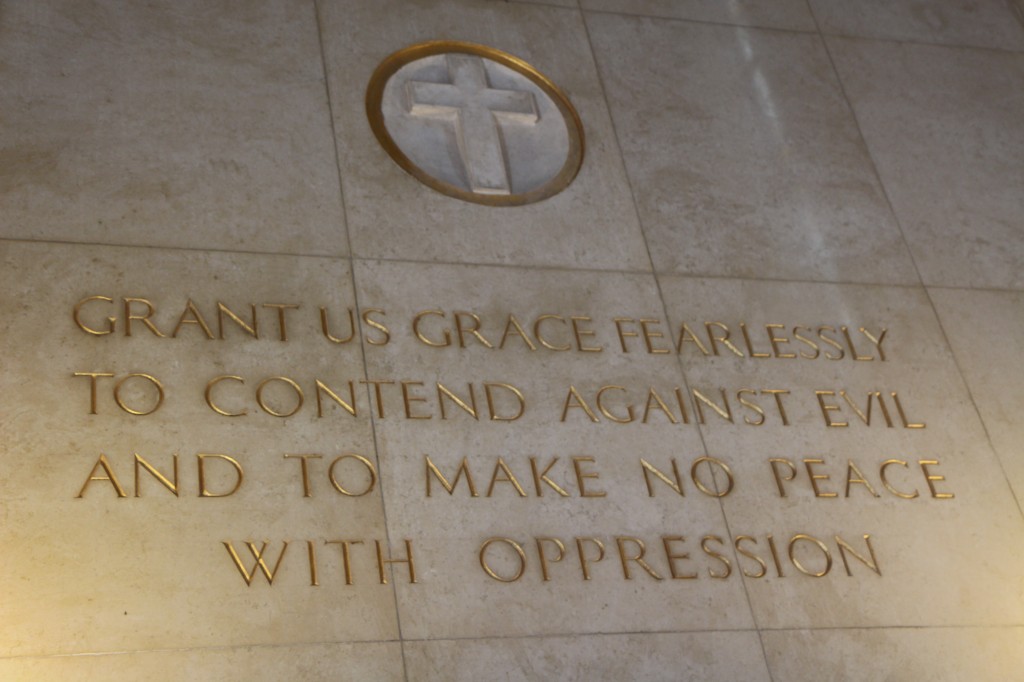

A chapel reaches towards the sky bearing the seal of the US and the inscription “1941-1945 In Proud Remembrance of the Achievements of her sons and in humble tribute to their sacrifices this memorial has been erected by the United States of America.” Inside, there is a tall, stained-glass window of the armies whose dead are held here. High above your head, a circular mosaic of angels paying homage to a dove and standing on the words “In proud and grateful memory of those men of the armed services of the United States of America who in this region and in the skies above it endured all and gave all that justice among nations might prevail and that mankind might enjoy freedom and inherit peace”. We try to leave some semblance of respect in the guestbook.

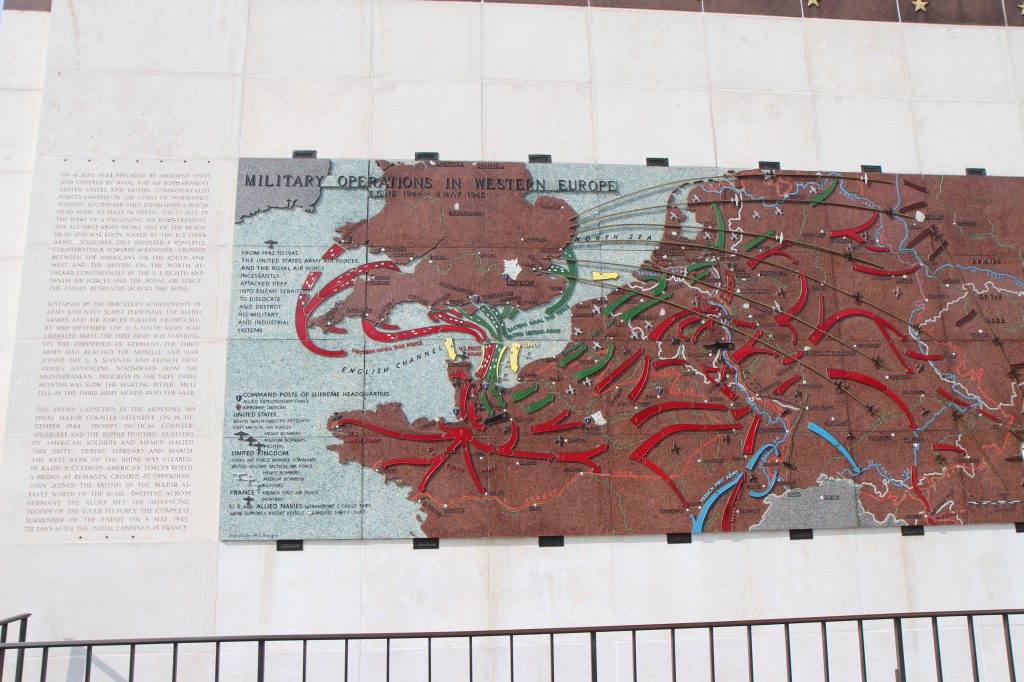

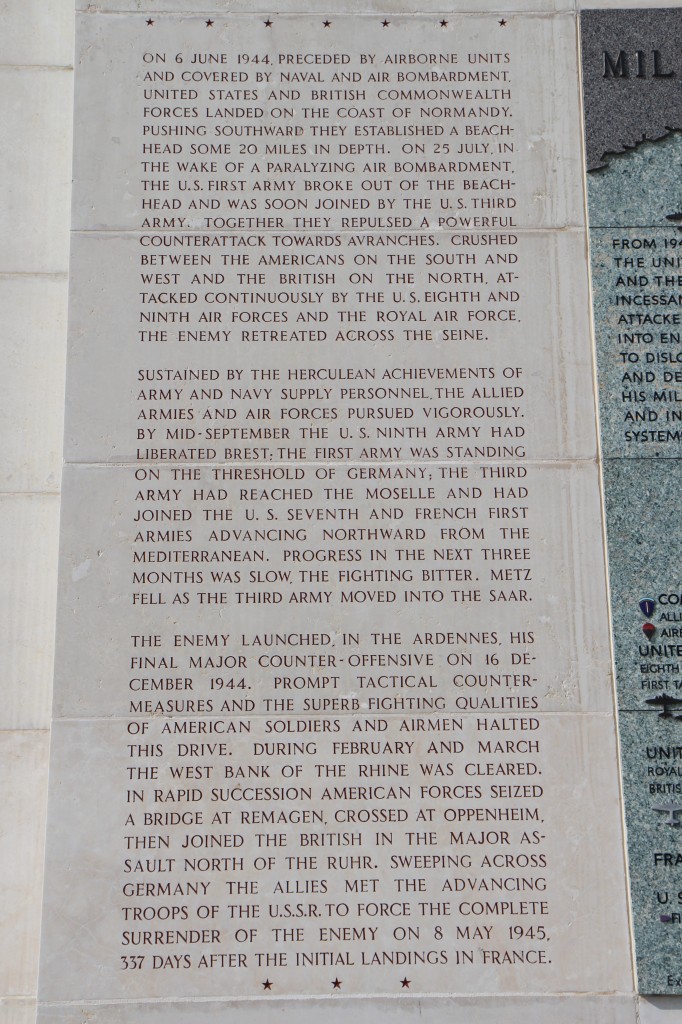

An enormous stone plaque spells out D-Day and its aftermath in Europe in both English and French. Another takes up the story of Germany’s last-gasp Battle of the Bulge beginning in December 1944.

We poke into the visitor’s center and meet the Luxembourgese man at the desk. Once he sees we are interested, he is quick to go the extra mile to explain the cemetery’s background. We talk quietly as the other half of the visitor’s center holds a small meeting chaired by the two American overseers of the cemetery.

US armed forces began burying soldiers here in December 1944 as the fighting still raged around them. The Germans shelled the construction of the cemetery until Patton told his troops to return eight artillery shells for every one the Germans sent the cemetery’s way. The shelling stopped. The dead primarily came from the fighting from this area during the bloody Battle of the Bulge. We are not far from Bastogne and Brig Gen McAuliffe’s—and his surrounded division in that battle— famous response of “Nuts” to the German request for the Yanks to surrender. The men were buried in bags and whatever was available as there were no caskets. We did not have the ability back then to quickly return remains to the States. Thousands were buried here, quickly.

The visitor center man shows us a book of pictures. The fresh mounds of earth rise before wooden crosses in December 1944. Another shows a shot of 1948 when the cemetery was transferred over to the stewardship of the American Battlefield Monument Commission. Every person was exhumed. Any family that wanted their loved one returned was obliged. They don’t know exactly how many were originally buried here but about sixty percent returned to their families in the States. Those left were reburied in sturdy, five-hundred-pound metal caskets. A picture shows them being reburied with either a pastor or a rabbi speaking over them. A crane lowered 5,076 back into the ground. Concrete beams were buried beneath the grass in concentric circles to bear the weight of the heavy headstones. Another picture shows a wreath laid by Winston Churchill on the grave of Patton.

We learn later that Lisa’s grandmother’s cousin is one of those who was sent back home.

Twenty-two sets of brothers lie here side-by-side. In just this one cemetery. A female nurse rests in peace here.

Two Medal of Honor winners rest here. Luke recounts one of the synopses to me. His name is Sgt Day G. Turner and his Medal of Honor citation is below.

“He commanded a 9-man squad with the mission of holding a critical flank position. When overwhelming numbers of the enemy attacked under cover of withering artillery, mortar, and rocket fire, he withdrew his squad into a nearby house, determined to defend it to the last man. The enemy attacked again and again and were repulsed with heavy losses. Supported by direct tank fire, they finally gained entrance, but the intrepid sergeant refused to surrender although 5 of his men were wounded and 1 was killed. He boldly flung a can of flaming oil at the first wave of attackers, dispersing them, and fought doggedly from room to room, closing with the enemy in fierce hand-to-hand encounters. He hurled hand grenade for hand grenade, bayoneted two fanatical Germans who rushed a doorway he was defending and fought on with the enemy’s weapons when his own ammunition was expended. The savage fight raged for four hours, and finally, when only three men of the defending squad were left unwounded, the enemy surrendered. Twenty-five prisoners were taken, eleven enemy dead and a great number of wounded were counted. Sgt. Turner’s valiant stand will live on as a constant inspiration to his comrades. His heroic, inspiring leadership, his determination and courageous devotion to duty exemplify the highest tradition of the military service.”

At least six members of Easy Company—of “Band of Brothers” fame—are here.

Are we teaching our generations about the bravery of these mighty men and women who stood up against tyranny?

The dead were buried as they came in. Entire cemetery sections list days of death as January-February 1945. The first tombstone Lisa reads lists the date of death as the date of birth of her mother, January 23, 1945. Her mother’s father stationed in the Pacific on the day she was born.

In all, 25 American military cemeteries reside in Europe with over 100,000 buried. Worldwide, we have over 200,000 Americans interred overseas after giving the last full measure of devotion. The American Battlefield Monuments Commission administer the cemeteries. The departed come from both World Wars and the Mexican-American War,

The cemetery is not far from the highway and down a side road. But it is quiet here. It is not warm, but somehow it is inviting. I notice a small group of similarly-dressed men carrying implements among the marble headstones. Upon closer inspection, we see the green uniforms of groundskeepers. They are tending to the grass. Later, we smell fertilizer. The same group of men, or possibly another, seem to continually buzz the roads in the five-acre cemetery with maintenance equipment. They drive around and I wonder if they are concerned about disturbing those who come to pay their respects, as if we might be visiting our grandfather. They are respectful but seem accustomed to this environment, as if they have seen this scene everyday. They have an oversized golf cart-type vehicle that holds lawn equipment, barricades and at least four men.

We wander down the concrete paths laid out around the dignified marble headstones. 5,076 heroes lie here. Over one hundred Stars of David mark the Jewish soldiers. Small stones have been left on many of the Jewish headstones, as a part of their tradition. We read that stones were originally left on Jewish graves to hold down notes and prayers left for lost ones. The notes would wither or blow away—leaving the stones. Over time, the stones became symbolic and a way of remembering their departed. We lean in over the grass, to strain to get a little closer to the names on the headstones. Flowers lean up against some of the graves. Christian crosses and Jewish Stars of David stand side by side. The headstones are of equal height and color.

I suddenly want to be closer to the headstones, and to take our family there. It seems too aloof to stand on the perimeter road, at a distance. We step onto the cushion of that soft, green grass. It is dewy or recently watered. We are closer to them now. Every state looks to be represented. We stumble across even Alaska, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana. We can read so many more names now. There are Army Air Corps men and many, many Infantry. A sea of headstones state the rank of private, some are TEC 4 or TEC 5, far fewer officers. We find a few TSGTs, a LT COL, a BRIG GEN, several LTs.

We stand before several known only to God.

We climb the gently-sloping hill of green dotted with white back towards the two, tall flagpoles. One grave lies between the flagpoles seemingly surveying his troops.

Concrete squares have been thoughtfully set in the grass to hold those who’ve stood before the grave of General Patton. He’d asked his wife to bury him with his solders and she chose this cemetery. He was killed in a senseless traffic accident with a US Army truck in December 1945.

A tour group and their French-speaking guide enter the monument and stand before the giant plaque maps. A group of German military men in uniform stroll beneath the eagle gates and stop to read the informational display sign on their way into the cemetery.

As we leave, the maintenance men carry on in their work. They don’t say anything to us but seem to be constantly moving. The grass is everywhere green and stands tall and trimmed to a consistent height. The headstones are white and in perfectly ordered concentric rings. I don’t see any of the green marks from grass cuttings so often thrown onto fence posts and street signs from string trimmers. The men have shown care. The flowers are in wonderful bloom. The colors of the grass, the flowers, the small fountains and the trees against the blue and cloudy sky look like the bold colors on an artist’s palette. The edges here are defined, they stand out from one another, they do not blur. All is clean, all is neat.

As we walk out to our car, Camille tells us how it makes her proud to see how our country remembers our soldiers.

It is overwhelming to see the respect lovingly meted out for our American war dead. These men, and one woman, are gone from the face of the earth, but not forgotten. Thank God our Nation still holds them close. War is terrible, we wish that none would seek glory in it. MacArthur said that it is the soldier above all others who prays for peace. I wonder, now, if it is the parents of the soldiers who pray even more.

After seeing Auschwitz, what can we say about these courageous men that stood up and gave all for others? How many families’ generations are shadows because of this terrible war? There must be enduring honor for those who fought the good fight. Great names are carved into the marble stones before us. They are giants upon the earth and it is humbling to think of their legacy in standing before the face of evil.

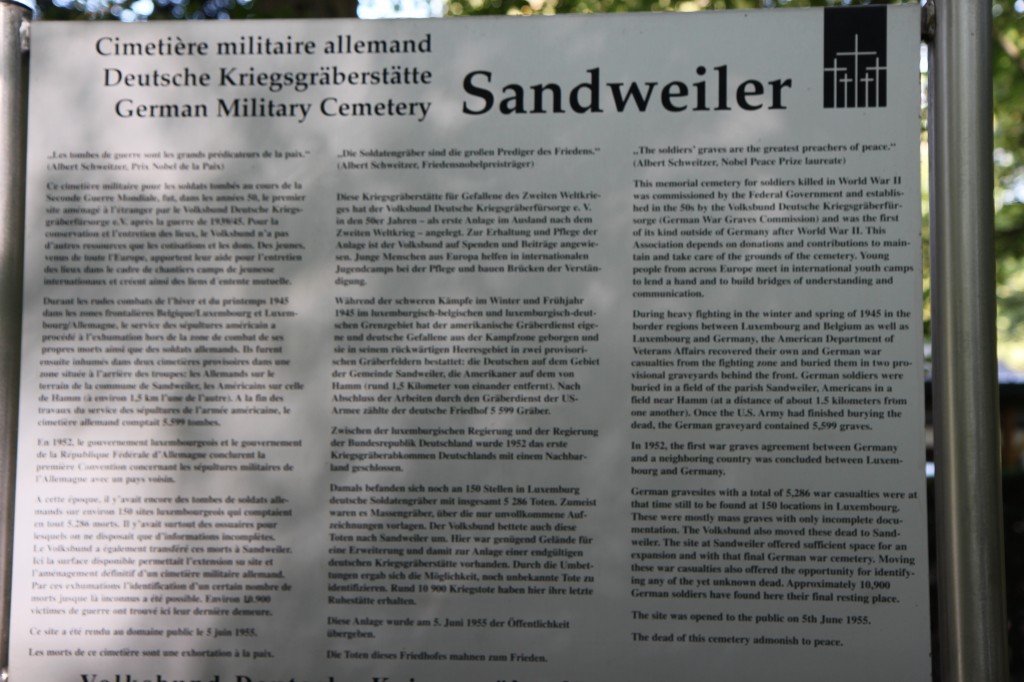

Back in 1944, the Allies also began to bury the German war dead in this region. The Americans and Germans who fought each other in the Battle of the Bulge are buried just 1.5 kilometers apart. I must give the benefit of the doubt here and I am no military historian. The Germans must have been retreating and unable to take care of their own. The Allies buried the Germans in groups of four. They must have noted their identities in some way. The Allies buried just over 5,500 Germans at the time. Years later, a German agency recovered about another 6,000 soldiers buried at over 150 sites in the area. Many of these men were buried in a mass grave at the back of the cemetery.

A high, dark stone wall marks the entrance of the German military cemetery. A narrow entryway focuses your attention onto the cemetery as you walk through the wall. We enter the unmanned Visitor Center office. A poster explains the German War Graves Foundation administers this site. I may have accidentally grabbed the English guestbook—we mainly see names from the USA and England—but we sign what we find. Since my German is non-existent, I am sure I am missing a lot.

An imposing stone cross towers over the rows of stones. A flagpole stands to one side of the cross. The flag must belong to the German War Graves Foundation. Heavy, grey headstones hold two names on one side and two on the other. There are many listed only as “Deutsch Soldat.” There are no Jewish star headstones. Though we saw a few cars in the parking lot, we seem to be the only ones here. The stones list birth and death dates. We find many in their late thirties and forties and many at just eighteen or seventeen years old. At such a late date in the war, the Germans were having to recruit deeper into their society. The elevated mass grave, behind the stone cross, has hundreds of names engraved into metal plaques. Beside the names of the deceased, there are very few clues this is a German cemetery. We wonder aloud if the Germans are not allowed to fly their flag here or have chosen to do so out of sensitivity to others. The German nation was devastated by WWII so it is unlikely their society had discretionary funds available for cemeteries after the war. There seems to be much here that we don’t understand and it is difficult to draw any conclusions.

It makes you wonder if any of these assembled Americans or Germans knew what was being done to the Jews at the camps.

For those who sacrificed so much for others, did they know what example they were setting for us in looking beyond ourselves? I am inspired by our family’s heroes when I think of the words of Proverbs.

“A good name is more desirable than great riches; to be esteemed is better than silver or gold.” —Proverbs 22:1